Here’s what we have seen thus far in our series on a theopoetics of Exile:

All humans feel an innate lack or void within ourselves. The serpent suggested to Eve in the Garden — and evangelicalism echoes this sentiment — that this sense of emptiness and incompleteness is not natural but foreign, and must be overcome by jumping through some set of hoops (eat this apple, pray this prayer, whatever). The crucifixion of Christ effectively put to death the old system according to which “God” is an idol who will bestow completeness and well-being upon us, having nailed those false hopes to the cross.

At this point it seems appropriate to talk a bit more about the death of Jesus and, more specifically, what is called “atonement theory.”

The reigning evangelical position is that Jesus died in order to pay the penalty for mankind’s sin. In this view, God the Father vented his anger upon his own Son and punished him in our place so that he could then show mercy to us (indeed, this view is so prominent that many evangelicals aren’t even aware that there are objections and alternatives to it).

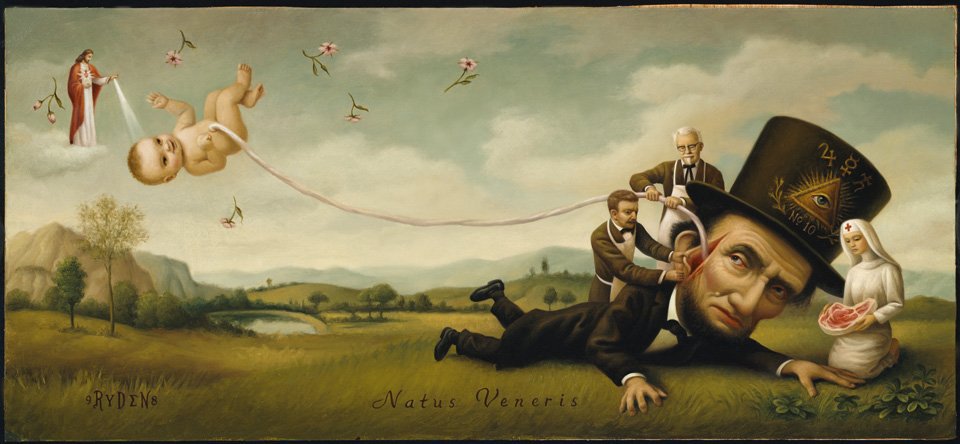

The reason Jesus needed to suffer at the hands of his Father, according to this view, is due to the holiness and unbending justice of God. Since God’s righteous character is expressed in his Law, and since we have broken this Law, God has no choice but to exact his retributive vengeance on someone. Since Jesus stepped in as a sinless substitute, God has gotten his “pound of flesh” by punishing his Son and is now free to extend grace to sinful humanity.

There are many problems with this position, but the one that I’d like to highlight is somewhat uncommon and seldom stated. Here goes….

I would suggest that this position fails to truly convey the cataclysmic shift from Law to Grace and from the Old Covenant to the New. In fact, it is actually a doubling-down on the forensic and legal arrangement of the old economy of Moses.

You see, by the evangelical’s insistence that God is only “able” to bestow grace if he first satisfies the bloodthirsty demands of a legal covenant, he is implying that there is some higher authority than God, namely, the Law. The Law, as it were, has power over God and hamstrings his efforts at mercy until, once its standards are met, it finally gives the go-ahead and green-lights the gospel.

In other words, it is really Law and not Grace that gets the final word.

A couple brief thoughts by way of response: (1) Perhaps the various efforts to “explain” the crucifixion, and the disagreements among proponents of these various views, are themselves proof that the crucifixion has no easy explanation. Paul referred to the cross of Christ as “a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles.” Maybe the best (and most humble) posture to strike toward this mystery is to simply let it be confusing and seemingly absurd? After all, if, as I have been arguing, there is a void and sense of meaninglessness at the very heart of life itself, then Jesus’ cry of dereliction at his seemingly senseless death is a perfect example of his participation in the emptiness and ambiguity that is the human experience.

And (2), the idea that God is somehow unable to simply forgive sinners, full stop, without getting legal authorization first is silly. Why not? And who says? If my son does a poor job of cleaning his room despite his best efforts, I as his father can just say, “It’s fine, buddy, don’t worry about it. You can go play now.” I don’t have to find some other child to step in and clean the room perfectly and then spank him for my own son’s crap job. I can just decide to accept the imperfect job my son did as good enough if I feel like it. After all, who cares? I love my kid, that’s what really matters.

To echo Jesus, if I as an earthly father can show grace to my son regardless of his performance, how much more will God show mercy to his children?

When we are confronted with the seemingly random and arbitrary nature of life, therefore, and find ourselves staring into the void, we can remember that Jesus faced the senseless violence and injustice of this world as well. And rather than “standing his ground” and saying “Don’t tread on me,” he suffered willingly in order to break the cycle of escalatory violence and show humanity a better way.

After all, if Exile is not merely a different (but equally imperial) alternative to Empire, but instead is a suspicion of that kind of power, then perhaps resisting the urge to explain the death of God (!) and letting it remain a weak and foolish mystery is the most consistent response to the matter.

I mean if Jesus himself asked “Why?”, who do we think we are?