We have been discussing the death of God and its effects, and I have hinted at how the notion of resurrection might be understood within this paradigm of Exile & Empire that I have been seeking to build.

Enough hints, let’s roll up our sleeves and dig in.

I will say at the outset that I am not arguing for or against the Dogma of the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ. I use the term “Dogma” deliberately, for as we have seen, the Church (capital C) defining Dogma (capital D) is an example of imperial authority and strong theology — in a word, it’s an expression of Empire. By its very nature Exile is suspicious of this.

Rather, what I want to offer is a reading of this event that comports with the Exilic posture that I have been exploring and seeking to strike.

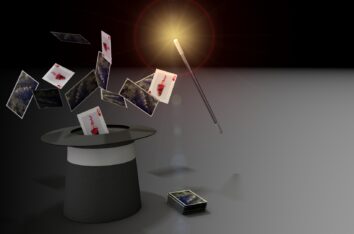

In an earlier article I alluded to the traditional structure of a magic trick to illustrate how the death of God functions within this paradigm: First is the Pledge, which is when the magician presents an object to his audience (the example I suggested was a coin). Next he does some hocus pocus and suddenly the coin disappears; this is called the Turn. Lastly is the Prestige, where the magician brings the object back, perhaps by lifting a glass from the table to reveal the disappeared coin underneath it.

Now of course, anyone at all familiar with sleight of hand will know that the coin that re-appears in the Prestige is a different coin than the one that vanished during the Turn. Most likely the original coin presented in the Pledge is now down the back of the magician’s shirt, while the coin revealed under the glass was there the entire time.

This is a crucial point to understand.

As we saw in the post linked to above, like the coin in our hypothetical magic trick, the Jesus who emerged from the tomb on Easter morning was similar to but significantly different from the Jesus who was laid there three days prior. Now it is at this point that I want to introduce a term and concept that are integral to all this:

Kenosis.

The concept of kenosis comes from the “Christ hymn” cited by Paul in Philippians 2:5-11, and the literal meaning of the term is “to empty.” So Paul says in v. 7 that Christ, rather than considering equality with God something to be “grasped” or “exploited,” instead “emptied himself,” taking the form of a servant and coming in the likeness of men. This kenotic, self-emptying act is central to my overall thesis.

We see a similar theme in Acts 2, where Peter addresses the crowd on the day of Pentecost regarding the supernatural phenomena exhibited among the members of the then-infant church: “This is that which was spoken by the prophet Joel,” explains Peter. He then quotes the prophet: “‘In the last days,’ says the Lord, ‘I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh.'”

Connecting this to a point I made earlier, as Christ died on the cross the Temple veil was torn in two from top to bottom, thus exposing humanity to the potentially lethal unmitigated holiness of the divine Presence. But rather than the expected outcome (something similar to that scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark when the Nazis’ faces melted off when similarly exposed), what happened was, well, nothing.

Putting all this together, therefore, an Exilic reading of these themes would suggest that perhaps the real point of the Gospel is not to get people up to heaven, but instead to help us realize that heaven itself has been emptied of divinity and that God is now truly Immanuel, “God With Us.”

This point is illustrated in the celebration of the Eucharist. First we have the Pledge, where bread and wine are presented. Then comes the Turn, when those elements disappear as we consume them. (In fact, it is very likely that when those early magicians would say “Hocus pocus,” they were subtly mocking the words of the priest: “Hoc est corpus” [meum] (“This is my body”).

But in the Prestige, the same elements of bread and wine don’t simply re-appear (just like the coin under the glass is not the same coin that vanished, and like the risen Christ wasn’t just the same old Jesus of Nazareth who died). Rather, the “body of Christ” that presents itself in the Prestige is us, his people, filled with the Spirit that has been “poured out on all flesh,” as we saw above.

In a word, maybe Paul was right (albeit perhaps only accidentally) and the only “God-Man” that exists for the world is you, is me, and is anyone who is willing to “fulfill what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ” in order to minister to a hurting world (Col. 1:24).