I’ve been doing a series of posts exploring the freedom one gains by unclenching a bit, epistemology-wise, and admitting that as Christians we should have more in common with the agnostic than we do either with the atheist who is certain God doesn’t exist or with the theist who is certain he does.

I’d like to take this idea out for a spin into dangerous terrain. But first, some set-up. . . .

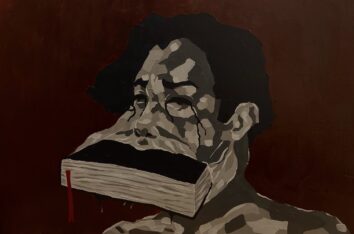

The way Christianity usually works is like this: We start with a series of doctrines that we consider “true,” mainly because they come from some source that we trust — whether that source is the Bible, the Church, our favorite guru, whatever. Then those teachings shape who we are, for better or worse (often for worse).

For example, when I was a staunch Calvinist I believed that mankind was wicked to the core from birth, and that God chose to save a small handful of chosen ones (among which [gasp!] I counted myself), and that this choice was based on nothing anyone does but was simply due to God’s arbitrary and inscrutable will.

These ideas shaped me. They shaped me into an asshole.

But here’s the thing: Since, in my understanding, those ideas were true (because they came from a true source) then whatever the practical results of them in my own life may have been, they were acceptable because they were the fruit of trustworthy doctrine.

Now here’s the subversive part.

What if we turned this process on its head, putting the practical cart before the theoretical horse? What if, instead of passively allowing ourselves to be shaped by external ideas imposed upon us from without, we began at the end, with the story of who we want to be, and then sought to reverse engineer a set of spiritual principles that were most likely to get us there?

What if we let the tale wag the dogma, and allowed our own personal story to actually shape what we believe rather than being determined by it?

For example, I want to be a compassionate and merciful person. I want to be open to a broad swath of ideas and lifestyles. I want to affirm and enjoy this world. I want to see myself in common with, rather than distinguished from, those whom I may consider strange or odd.

I don’t want to be an asshole anymore.

So rather than idly accepting dogma that is forced upon me by some external authority, why not just adopt ideas that are most likely to shape me into the person I already know I want to be?

After all, doesn’t the Good Book itself say that at the end of the day, what really matters is whether or not I love my neighbor (Gal. 5:14)? Therefore shouldn’t any proposed idea or doctrine that threatens to make me less loving and compassionate be rejected simply on that basis?

Discuss. . . .