As you may know, the Misfit Faith podcast is doing a series on the Bible titled “Thoughts on the Good Book,” and my guests so far have been Brad Jersak and Jared Byas. In the spirit of this series I’d like to briefly set forth a few propositions for the consideration of anyone who is struggling to navigate their relationship with Scripture in a post-evangelical context.

1. If you hold to the existence of a personal God who is described in the Old and New Testaments, it is not unreasonable to insist that this God is like Jesus (as in, exactly like him). This means that when you run across divine portraits in the OT that make God appear capricious or cruel, and if you can’t imagine Jesus having acted in that way, then it is safe to assume that God didn’t act that way either. The event either did not happen the way the author describes it, or it did happen that way but God had nothing to do with it.

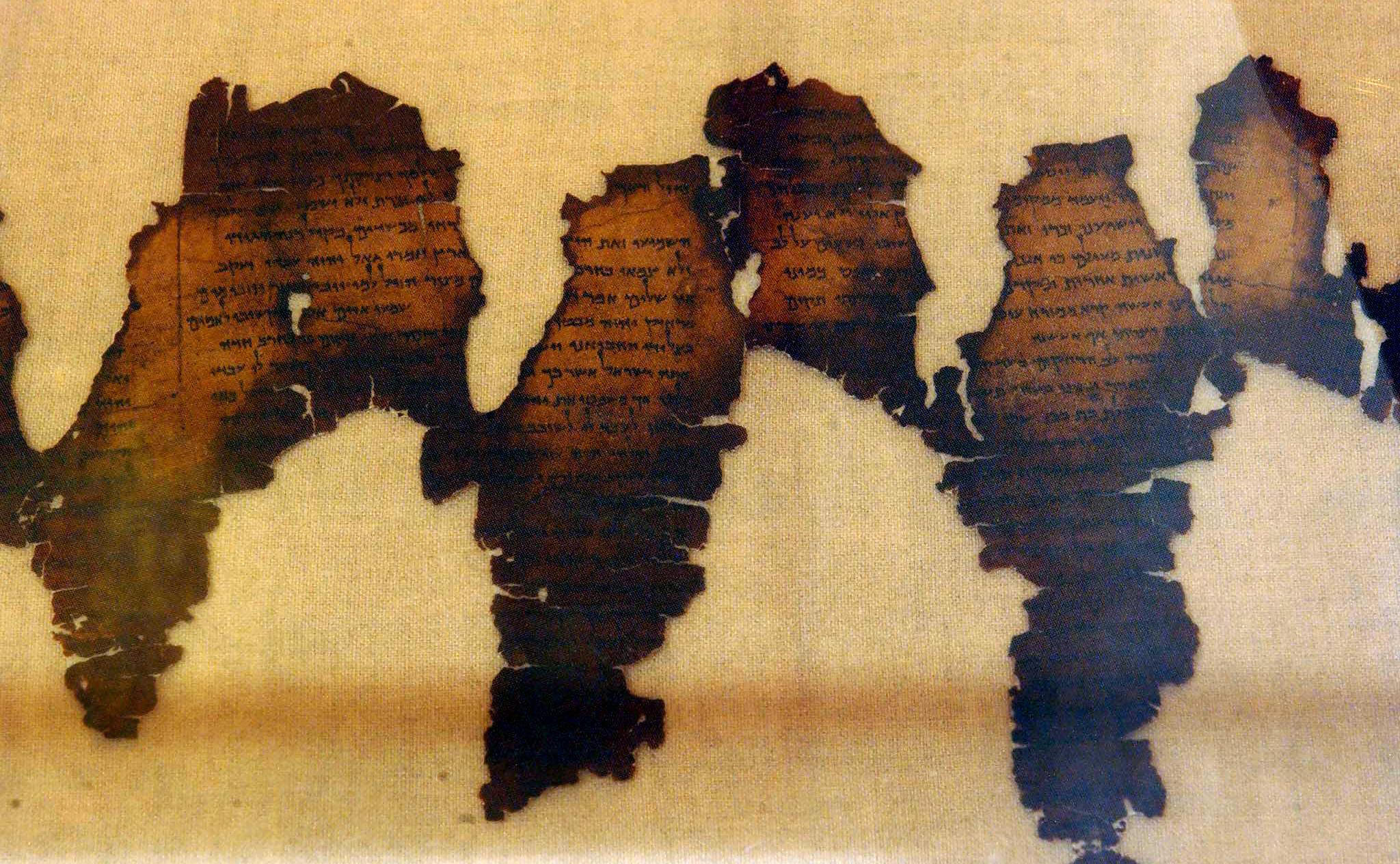

2. The purpose of ancient Near-Eastern oral or written accounts — whether of creation, conquests, or whatever — was not to “do history” the way we do in the modern, post-Enlightenment West (which usually involves seeking to reconstruct as accurately as possible “what really happened”). Rather, in antiquity people employed narratives and stories as a means of contextualizing and legitimizing their own tribe or nation among the other rivaling people groups around them. The lack of any archaeological evidence, therefore, for a biblical event like the destruction of Jericho (or of the Canaanite conquest more broadly) is not a huge problem. The purpose of Joshua’s accounts, after all, was not for him to earn a doctorate in trans-Jordanian history from his panel of dissertation advisers at the University of Mesopotamia, it was to explain to future generations how Israelites are to understand themselves and their place in the land which they came to inhabit.

3. Lastly (to borrow from my conversation with Jared Byas), “God lets his children tell their story.” In a similar way to how a child on the playground at school might brag about how his dad is a black belt in karate and can lift a truck with one hand, so God’s people can be forgiven for embellishing their own history and peppering it with accounts where a fortified city’s walls come a-tumblin’ down at the blast of trumpets and priests can make the sun stand still until Israel’s army has won its victory over their pagan enemies. Indeed, a case can even be made that when God lets his image be tarnished by allowing his sinful children to attribute to him such cruel violence, it is an act of divine grace and condescension, not unlike Jesus allowing his literal physical appearance to become marred by the sinful violence of those who beat him, flogged him, and nailed him to a cross.

In summary, having a healthy appreciation for the Bible doesn’t mean we must defend all the horrific violence contained therein, even when it’s supposedly God who’s behind it.